The Common App first moved online in 1998 and since then has had a profound impact on the higher ed application landscape. For one, it has been extremely beneficial in terms of making the application process more accessible to a larger number of students and providing them with an abundance of information about institutions and the application process. However, as the Atlantic notes, “While schools might welcome the rush of national exposure from a broader pool of prospects, they also increasingly face the problem of sorting out applicants who are both a match for the school and would also enroll if accepted.” Moreover, this influx in applications could “exacerbate undermatching, where high-quality lower-income candidates are channeled into less-selective schools.” Despite these consequences, the Common App has, without a doubt taken the application landscape by storm. This post will explore the Common App in relation to the rise in college applications and whether or not that has enabled schools to diversify their applicant pools.

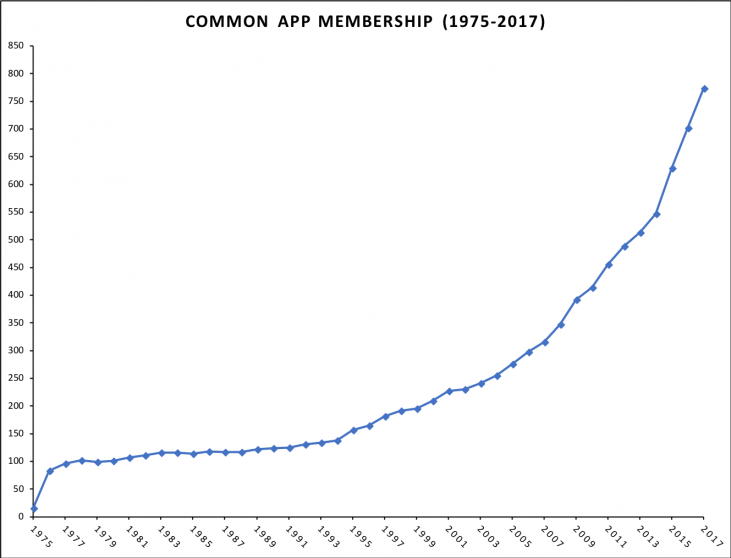

The Common App began in 1975 with the goals of increasing access and equity in the admissions process and streamlining the complicated college application for students, and it has since grown to be of strategic use and importance to colleges and universities. The Common App has seen tremendous growth since its inception. It started with just 15 college and university members. Today, there are over 750 institutions that accept the application, and according to the Common App’s website, “each year, more than 1 million students use the Common App to submit more than 4 million applications.”

Common Trend

The Common App has established itself as a nearly obligatory part of the application process for students and admissions strategy process for colleges and universities. The Chronicle of Higher Education wrote in 2010 that, “among the most-selective colleges, the decision to adopt the application seems almost inevitable—a question of when, not if.” The article went on to say that, “In 2008, the University of Chicago, long known for its distinctive Uncommon Application, joined the party after years of principled objections. In 2010, Columbia University hopped onboard, becoming the last member of the Ivy League to do so.” A critical factor behind the increase in Common App membership over this time was the subsequent rise in the number of applications these institutions observed.

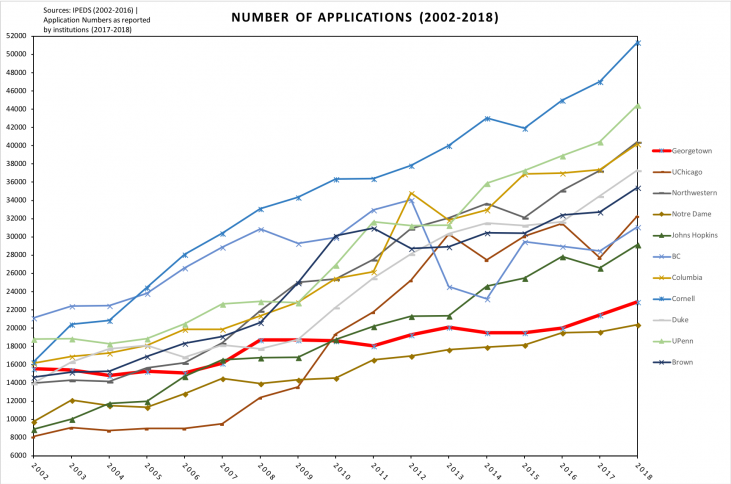

Interestingly enough, the year in which a school joins the Common App shows an upward trend in the number of applications across the institutional landscape. While noting the numerous other variables at play, this upward trend, in part, might be from the ease with which students are able to “add” another school to their applications. The graph below shows the number of applications submitted to Georgetown (not a Common App member) and its peers – who are Common App member schools – from 2002 to 2018. Georgetown’s student application numbers stay relatively consistent while, for example, the number of applications to Cornell went from 20,822 in 2004 to 24,452 in 2005.

One additional aspect to consider when thinking about the Common App’s impact is the rate of growth in the number of applications in relation to the growth of the undergraduate population. The National Center for Education Statistics reported that from 2000-2016, the total undergraduate enrollment in postsecondary institutions increased by 28 percent. Moreover, undergraduate enrollment increased at private nonprofit institutions by 27 percent. So it should be anticipated that there would be an increase in the number of applications submitted over the same period of time, however, not by as much as the 150 to 200 percent increases depicted in the application numbers above. Georgetown in the graph above might offer a glimpse into what the real increase in apps over that 16 year period and begs the question, what could’ve been had it joined?

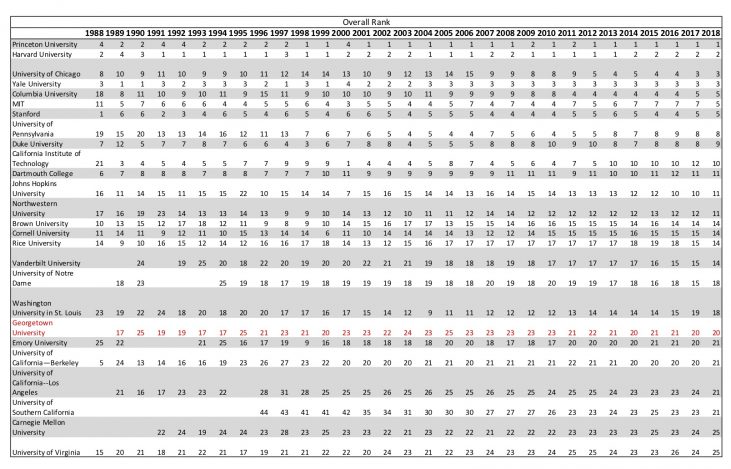

At this point it could be that since the admissions landscape now includes the Common App, its effect has been diluted and Georgetown sees the same return that the institutions that joined in the 2000’s saw. That said, if Georgetown were to join the Common App then it would most likely see a 5 percent increase in the number of applications received, which Liu, Ehrenberg & Mrdjenovic (2007) find in their study that is discussed below. The increase in the number of submitted application would, as a result, drive selectivity and rank. In this regard, Georgetown’s decision to not join the Common App is having a negative impact. Despite not adopting the Common App, Georgetown remains competitive in the rankings and continues to attract a diverse pool of applicants through its all-in commitment to diversity and educational opportunity. The figure below shows the US News & World Report Undergraduate Rankings from 1998-2018. As you can see, except for a few institutional outliers, rankings oscillate plus or minus a few spots but largely remain stable over the 30 year period. During the 2000’s when the majority of the top institutions adopted the Common App, Georgetown’s rank stayed around 20th. Clearly, Georgetown appears to be holding its own as one of only two schools – MIT being the other – in the top 25 not on the Common App. It’s safe to say, with regard to the top 25, once you’re in, you’re in.

Diversity through a Common Approach

It’s clear that the Common App helped to facilitate the ease of applying to college, but has it diversified the applicant pool? Liu et al. (2007) explore the diffusion of Common App membership among private postsecondary institutions and find that Common App membership increases applications by 5.7 to 7 percent and admittances by 4.3 to 5.9 percent. Their research suggests that Common App membership enables an institution to enroll a more diverse applicant pool, which, to some degree, supports progress towards the Common App’s intended goal of increasing access and equity in the admissions process. However, contrary to the Chronicle of Higher Education article above, considering Liu et al. (2007) data reflects matriculants and not applicants, which makes it hard to differentiate the Common App’s effect from an institution’s strategic mission towards diversity.

Another notable study, Smith, Hurwitz & Howell (2014), acknowledges that the postsecondary marketplace has structurally evolved to become more competitive over time. Smith et al. (2014) investigate the extent to which students respond to small costs associated with the application screening process, specifically application essays and fees.1 While they conclude that Common App membership yields no observable impact on the number of applications an institution receives, their data suggests otherwise. The data appears to be consistent with Liu et al. (2007) and shows that Common App membership increases the number of applications by 3.5 percent. Moreover, their data depicts that Common App membership is associated with a 5 and 4.3 percent decrease in first generation students and low-income students, respectively. This would mean that Common App membership might actually hinder diversity in the applicant pool.

Common Consideration

The Common App has and continues to be integral to an increasing number of colleges and universities. However, the extent to which it diversifies the applicant pool is at best circumstantial. Moving forward, further research should be conduct into the student level impacts of the Common App. Klasik (2012) notes that, “Despite the Common Application’s popularity and potential impact on student application choices, it has received little scholarly attention, and what exists has focused on its strategic adoption by postsecondary institutions and the benefits those institutions reap. While it is important to understand the institutional impact, this focus has drawn scholarly attention away from analyzing the Common Application’s impact on its intended and primary consumer: the student applying to college.”

For schools who are not Common App members, it might be worth considering if there is an application platform that is more aligned with the school’s approach to diversity and equity in the admissions process. For one, the Coalition for College offers one possible alternative admissions strategy/application platform to the Common App. Although a dearth of research on the Coalition currently exists, at a glance, the Coalition appears to be more accessible for students and provides them with much more control when applying to college. This application platform might prove to be a viable substitute to the Common App when considering how to best assist and inform students in the difficult process of applying and matriculating into a college or university that is a good match.

1. Findings not discussed: Increase in Black and Hispanic students 5.6 percent though 6.6 percent decrease when competitor adopts. Big decrease in fed financial aid when competition adopts Common App.↩

Author:

Mark Joy: Senior Research & Programs Associate for The Hub for Equity and Innovation in Higher Education

0 comments on “A Common Thread”